So it’s the start of a new semester, and after having sworn off Netflix for good, you’re sure you’re going to earn your best GPA yet. But what steps can you take to make sure you get there? Read the tips below to find out!

1. Actually Go to Class

Show up every day, on time. You’d be shocked at how many students fail to meet this bare minimum!

2. Stay Off Your Phone. Stay Off Your Laptop.

Yeah, it’s tempting, and it’s sooo easy. But don’t be rude and don’t be distracted. Even if you’re taking notes on one, laptops give off a vibe of disinterest. Better stick to pen and paper, if you can.

Yeah, it’s tempting, and it’s sooo easy. But don’t be rude and don’t be distracted. Even if you’re taking notes on one, laptops give off a vibe of disinterest. Better stick to pen and paper, if you can.

3. Read the Material

This seems obvious. However, a little reading every night will soon get you not only caught up to the class material, but beyond it. Once it’s a habit, it will feel weird not to read. Make a Buster-esque contraption to keep you awake, if you must.

This seems obvious. However, a little reading every night will soon get you not only caught up to the class material, but beyond it. Once it’s a habit, it will feel weird not to read. Make a Buster-esque contraption to keep you awake, if you must.

4. Go to Office Hours

Professors love when you go to office hours. LOVE. They can talk and help you out so much more when they have your attention past the mandatory 3-hours-per-week. And if you’re in an upper-level math class (speaking from experience here), you’ll never get an A without this.

Professors love when you go to office hours. LOVE. They can talk and help you out so much more when they have your attention past the mandatory 3-hours-per-week. And if you’re in an upper-level math class (speaking from experience here), you’ll never get an A without this.

5. Participate At Least 1x/Class

Don’t be that student and talk all of the time, but put yourself out there and thoughtfully ask or answer a question each class meeting. Your professor will remember you as a reliable class contributor.

Don’t be that student and talk all of the time, but put yourself out there and thoughtfully ask or answer a question each class meeting. Your professor will remember you as a reliable class contributor.

6. Start on Homework Early

I know, I know—It’s a drag. But planning out and starting your assignments early leaves you more time to polish your work and review it with the professor.

7. Grab a Study Buddy

Exchange contact info with someone in the class, and set up times to study together. This keeps you accountable for studying and getting classwork done. It also helps you get caught up if you miss a class.

8. Ask Your Professor

Your professor knows best how to do well in her course. Ask early on (as opposed to a week before the final) and phrase it as, “How can I be most successful in your class?” Be sure to take notes–and then follow through!

9. Use School Resources

…such as the Writing Center! We’ve got your back. With 19 peer tutors and counting from many different academic disciplines, you’re sure to find someone to help you plan out your writing and double-check your work.

Above all, do your best. Even if you don’t get an “A,” you’ll feel good about all of the effort you put in. You may even surprise yourself!

Good luck with your semester!

-Peer Tutor Sarah C.

Have you ever wanted to write about the experiences you’ve had when you’ve travelled? Maybe you went to Punta Cana this past summer, or England on your Jan Term. How can you let someone know what your experiences were really like? The answer to that question is: travel writing.

Travel writing is a genre of nonfiction writing in which “the narrator’s encounters with foreign places serve as the dominant subject.” This means you can write about exploration, adventure, or the great outdoors! But you can also write about not-so-glamorous experiences, like riding the broken-down metro or getting lost in the back alleys of Budapest. Anything that’s a “travel experience” is fair game. It’s also important to note that you don’t have to travel far to have a meaningful travel experience. You can travel write about your hometown: What is there to do? What aspects of the town do people first notice? What’s the attitude of the people like? Your backyard is someone’s travel spot!

Not your literal backyard, though.

Interested yet? Well, onto the first step: travel there! If you have yet to go to your destination-of-choice, be sure to bring a journal when you do. Jot down notes about things that strike you. What are your first impressions? What makes the place unique? What is an encounter that might be interesting or amusing to retell? If you have already been to your destination and are writing about it after-the-fact, try to mentally travel back to that place, and ask yourself the same questions: What features of the place stood out to you? What vibe did you get from the people? Did anything interesting happen to you while you were there? Describe it! As an aside, your writing doesn’t have to be an encapsulation of an entire place. You can travel write about things like a restaurant, park, or mall (while eventually putting it in the larger context of the place—but we’ll get to that!).

Next, organize your notes. For travel writing, you’ll usually want to have a mix of:

- your own present experiences in the place

- your past experiences relevant to the place

- experiences of other people in the place

- historical or broader context about the place

This “weaving” of different content allows you to give a fuller picture of the place to your readers. It keeps things interesting without relegating your writing to only a quirky story or an encyclopedia entry. Including people (whether it’s yourself or others) interacting with your place also prevents you from simply describing the physical features of a place, which gets boring fast.

If you need help with details and organization, check out some “travel” shows like Rick Steves Europe, House Hunters International, and Diners, Drive-Ins, and Dives. These shows profile places visually and orally. The writers find interesting features of a place, film and talk about them, and give background information. Take note of how they do it, and imagine you’re a director: how would you film your topic? You can’t include everything, so what do you include?

Finally: write! As with any writing: draft, revise, repeat—until you have an engaging and informative piece that illuminates some aspect of your place. Do this well enough, and you can even submit to magazines and get paid! At the very least, you will have a great written memory of a place and your experiences there.

-Sarah, peer tutor

Have you ever gotten an assignment from a professor, planned out when you would begin it, and sat down at your freshly-cleaned desk with your laptop, a drink, and a healthy snack, only to find that you don’t understand the instructions?

This happens to everyone at some point. Sometimes professors’ instructions are vague (perhaps purposefully so); sometimes their prompts are multi-faceted and open-ended; sometimes the assignment is separate from the class material and therefore difficult to begin working on. Whatever the reason, writing assignments can be murky to navigate. So what should be your first resource (besides The Writing Center)? Your professor.

Talking to your professor can be intimidating, but the reasons why it can be intimidating are the same reasons why it can also be helpful. Your professor has an advanced degree and years of experience in their field. Their job is to be a resource. Also, your professor is the one reading and grading the assignment. They came up with it. They know what they’re asking you to do.

Image from flickr.com

So how should you go about contacting them for help? The answer is professionally, honestly, and sooner rather than later! Some professors have their preferred method of contact listed on their syllabi; usually this will be their office hours. If not, they probably prefer to communicate by email.

When you attend office hours, come prepared with specific questions about your assignment. What is it that you understand, and what is it that you don’t? Is a particular instruction confusing or vague? Are you uncertain about what the assignment is referring to? If your questions are numerous or don’t fall within the scope of what is covered in class, consider asking your professor for resources you can use to help you with the assignment (for example, The Writing Center often refers writers to the Purdue O.W.L. for help with citations!). If office hours don’t fit into your schedule, then try email—again including specific questions about the assignment.

Image from flickr.com

If you are able, it may even be best to draft your assignment (perhaps with help from The Writing Center) and then show it to your professor (well in advance) for feedback. You can find out what you’ve done right and what you need to improve upon—and besides, it shows effort!

Here at The Writing Center, we’re happy to help you break down your assignment, draft your writing, and contact your professor. After all, communicating is what we do! So don’t put off your next assignment because you don’t understand—get started today. (link to writing center website there)

-Sarah, peer tutor

Stuck in a creative rut? Collapsing under the weight of seemingly endless papers? Or are you simply wondering how music can relate to writing? Here’s what you can learn from one of the best (song)writing duos of all time, former Beatles John Lennon and Paul McCartney.

From http://fadedandblurred.com/spotlight/linda-mccartney/

Space.

When given a writing assignment, allow yourself some space for reflection, if you have the luxury. It took John Lennon several weeks to draft I am the Walrus before he found his muse.

“I had just these two lines on the typewriter,” he said,” and then about two weeks later I ran through and wrote another two lines, and then when I saw something after about four lines I just knocked the rest of it off. Then I had the whole verse or verse and a half and then sang it.”

Even for world-renowned writers, sometimes inspiration will hit when you least expect it. Keep an open mind.

Collaboration.

Bounce ideas off of someone! Your roommate, your professor, your friends… you never know what someone else has to contribute. John Lennon and Paul McCartney wrote songs together for over ten years, and they’d tell one another when something worked and when it needed to be changed. John said once that Paul’s musicality really impacted his own songwriting, and in return, John helped Paul lyrically:

“[Paul would] say, ‘Well, why don’t you change that there? You’ve done that note 50 times in the song.’ You know, I’ll grab a note and ram it home. Then again, I’d be the one to figure out where to go with a song… a story that Paul would start.”

And Paul still works with John: the bassist recently said that when he finds himself with writers’ block, he tries to imagine what John Lennon would do:

“If I’m at a point where I go, ‘I’m not sure about this,’ I’ll throw it across the room to John. He’ll say, ‘You can’t go there, man.’ And I’ll say, ‘You’re quite right. How about this?’ ‘Yeah, that’s better.’ We’ll have a conversation. I don’t want to lose that.”

So have a discussion—even with someone imaginary—whose opinion you respect.

Progress.

Look to your prior work in your discipline for inspiration and encouragement.

“It’s funny,” John once said, “because while we’re recording we’re all aware and listening to our old records and we say, we’ll do one like The Word– make it like that – it never does turn out like that, but we’re always comparing and talking about the old albums – just checking up, what is it? like swatting up for the exam – just listening to everything.”

It’s important to review your past papers—you might get a sense of accomplishment in addition to some new ideas.

Dissatisfaction.

Accept that sometimes, some papers will be less interesting than others, and you might not feel proud of them. John Lennon experienced the same with particular songs:

“Good Morning, Good Morning, I was never proud of it. I just knocked it off to do a song.”

There will always be other papers. Just do your best!

Self-reliance.

John said,

“In the early days, we’d take things out for being banal, clichés, even chords we wouldn’t use because we thought they were clichés… going right back to the basics [has been a great release for all of us.] Like on Revolution I’m playing the guitar and I haven’t improved since I was last playing. But I dug it. It sounds the way I wanted it to sound.”

Have confidence in what you know. Don’t try to beef up your writing with unnecessary clichés or complex words that you wouldn’t normally use. That’s not to say you shouldn’t try to improve, but sometimes the best writing comes from you and you alone.

Time.

This is perhaps most important. John once said of The Beatles early days, “We knew what we wanted to be, but we didn’t know how to do it, in the studio. We didn’t have the knowledge or experience.” It sounds cliché, but it takes time to write well. Keep trying. The Writing Center has got your back. \m/

———————-

Sources:

Read More: Paul McCartney Still Gets Songwriting Advice From John Lennon

Read more: John Lennon interview at Rolling Stone

———————-

–Sarah C, peer tutor

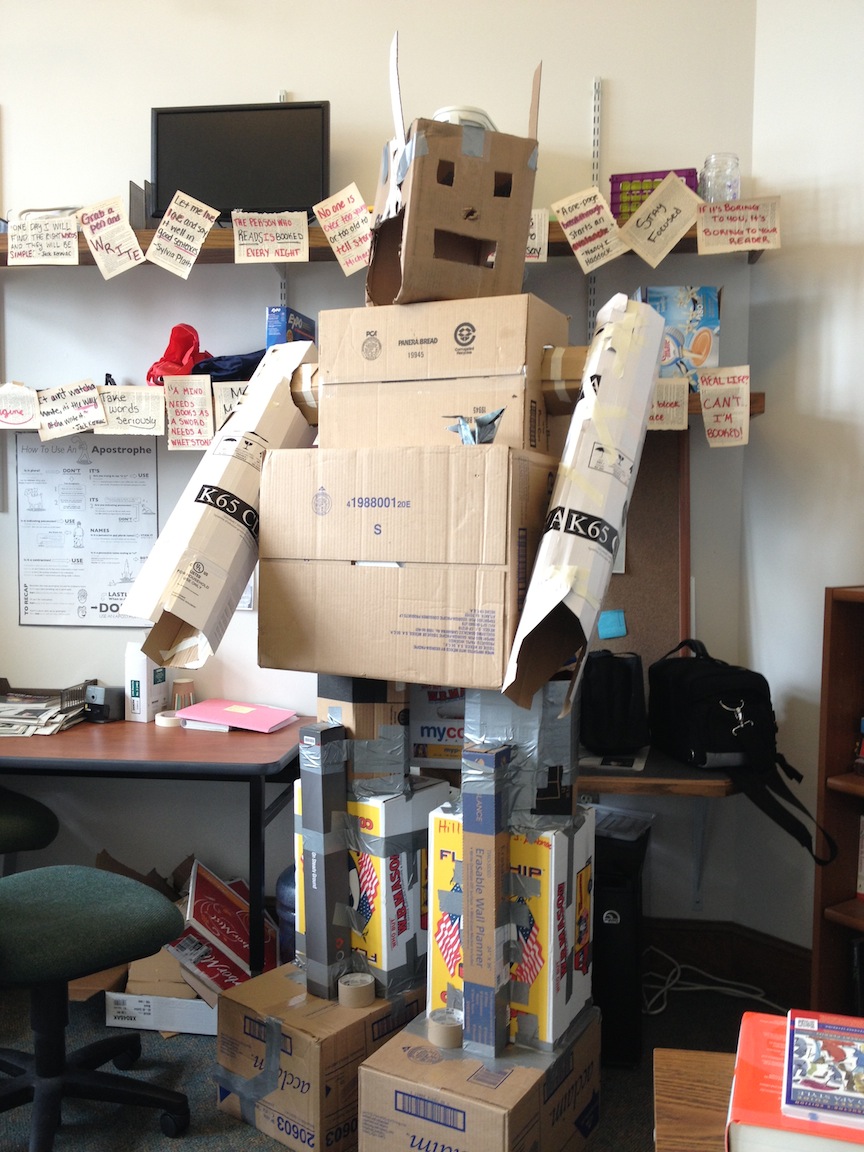

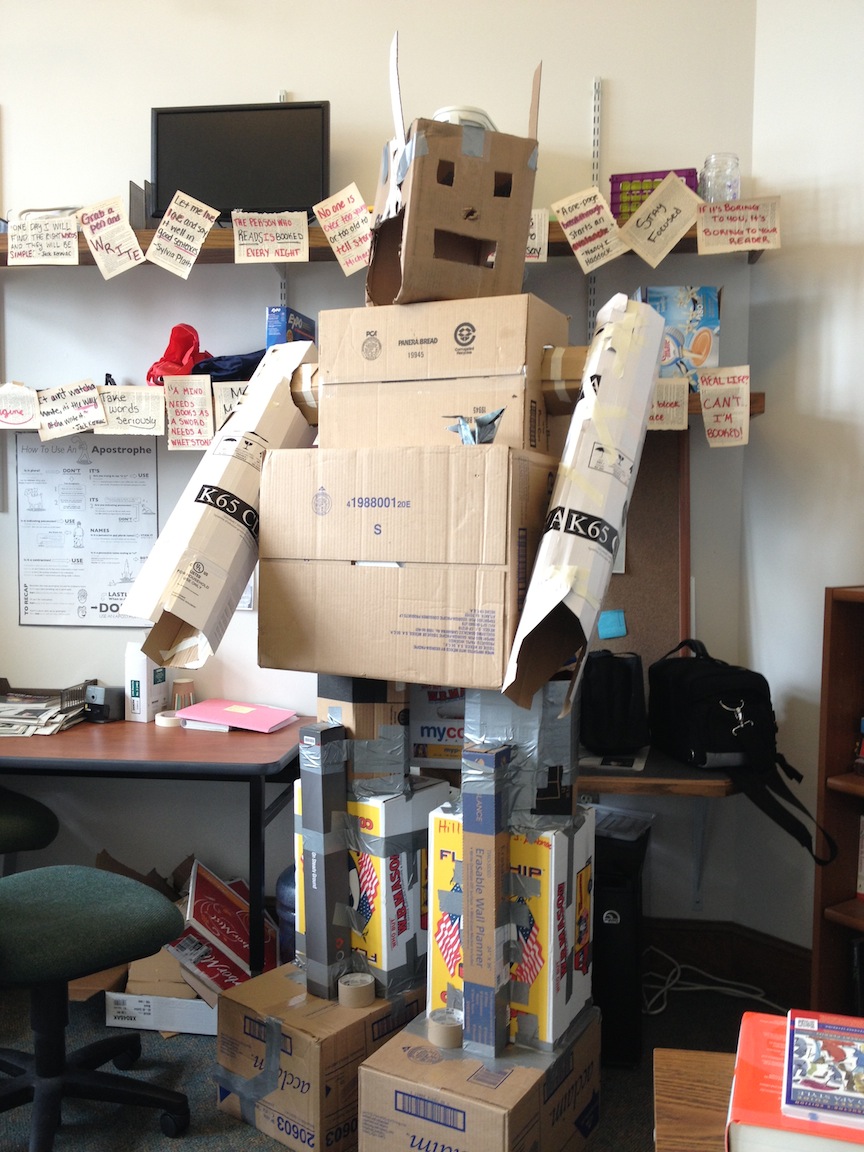

Robots love commas.

Commas aren’t some piece of punctuation meant to aggravate you. They can actually be used as rhetorical tools, meaning that you can use them to emphasize information. Commas can also help you add clarity to your writing so you don’t confuse your readers.

Commas separate, introduce, and show information. While comma rules aren’t completely rigid, there are some comma guidelines that you should be familiar with. Once you get to know these, you can begin to mess with them to suit your rhetorical needs.

HOW TO USE COMMAS

There are four cases when you should really use commas:

1. To separate clauses. Commas often separate an independent clause (a phrase that can stand alone as a sentence) from a dependent clause (a phrase that can’t stand alone).

- When the robot was first built, he didn’t have any legs.

2. To separate parenthetical phrases. Parenthetical phrases interrupt other phrases or clauses, and contain extra information that could be removed from the sentence without changing the sentence’s core meaning.

- The robot, which had no name, was created to guard and protect the Writing Center.

3. To separate introductory phrases. An introductory phrase is a phrase at the beginning of the sentence (usually a dependent clause) that provides background information for the main sentence.

- While the robot was painted silver, he had a heart of gold.

4. To balance two independent clauses (with a coordinating conjunction). Two independent clauses can be two separate sentences, or can be combined into one sentence using a comma and a coordinating conjunction (and, but, or, yet, for, nor, so).

- Students loved the robot, for he was kind and generous.

- The robot enjoyed getting to see the students, but he was always sad when the Writing Center closed for the night.

- The tutors realized how lonely the robot was becoming, so they built him a robot dog to keep him company.

HOW TO NOT USE COMMAS

Even though there is a lot of flexibility in what ways you can use commas, there are also cases when you should avoid using them:

1. Don’t separate the verb from its subject or its object.

- The robot, danced when no one was looking. → The robot danced when no one was looking. (The robot is the subject, danced is the verb.)

- The robot walked, his robot dog. → The robot walked his robot dog. (Walked is the verb, his robot dog is the object.)

2. Don’t use a comma between an adjective and a noun.

- The cardboard, robot was always eager to help students with their writing. → The cardboard robot was always eager to help students with their writing.

3. Don’t use a comma before the first item in a series.

- The robot likes, gummy worms, break dancing, and paper cranes. → The robot likes gummy worms, break dancing, and paper cranes.

4. Don’t use a comma after a coordinating conjunction.

- The robot was large yet, gentle. → The robot was large yet gentle. *OR* The robot was large, yet gentle.

Note: You can use a comma before the coordinating conjunction if you want, but you don’t have to, since the two clauses are not independent clauses. Whether or not you put a comma before the coordinating conjunction in cases like this will depend on how much you want to emphasize the piece after the conjunction.

≈ ≈ ≈ ≈ ≈ ≈ ≈ ≈ ≈ ≈ ≈ ≈ ≈ ≈ ≈ ≈ ≈ ≈

We hope this rundown of good and not-so-good uses of commas is helpful for you. If you have any more punctuation questions, feel free to stop by the Writing Center or schedule an appointment here.

We also hope that you’ll stop by and check out our new giant cardboard robot—he still needs a name and we would love your input!

—Annie and Sarah, peer tutors

It’s that time of year again: the sun is shining, the birds are chirping, and you’re sitting at your computer, furiously preparing those applications for summer jobs and internships.

Ah, the life of a college student. (source: learnnotto.soup.io)

Job applications themselves tend to be straightforward. More often than not, the trouble arises when it comes time to talk about yourself in a formal way. That’s right: statistics show that resumes (and their partners-in-crime, cover letters) pose a challenge for 75% of the population.*

*Note: all statistics in this blog post are made up by the author.

So how do you overcome this? How do you present yourself in a way that will have companies begging you to work for them? Take a look at the tips below.

The Bulk

In any resume, you want to answer three main questions:

1. What have you done?

2. What are you doing?

3. What do you want to do? (This one is sometimes optional.)

To answer the first and second questions, you will want to list your educational qualifications as well as past jobs and volunteer positions you’ve held. You also want to describe your duties in these positions, in such a way that the qualities you’ve developed at these jobs shine through and say to your employer, “Hey, look at what I learned! I can bring this skill to your organization!”

Don’t do this. (source: http://pandawhale.com)

Resumes often contain an “objective statement” to answer the third question. This is a one-sentence statement about your goal for employment. It should express to your potential employer what you aim to accomplish in applying for this job. For example,

• Summer Camp Counselor: “To facilitate friendships and a love of learning in a stimulating camp environment.”

• Arts Administration: “Position with community-based arts organization involving public relations, marketing, and promoting performances and exhibits.”

• Computer Programming: “Programmer or systems analyst position using quantitative and mathematical training, with special interest in marketing and financial applications.”

As a wise former writing tutor once said, “Your objective is like the thesis statement of your resume.” So make it clear and make it stand out to your potential employer!

The Beauty

Resumes need to be beautiful (but sort of in the way that contemporary industrial architecture is beautiful).

The hard angles convey a sense of order, while the neutral tones suggest sophistication. (source: http://www.urbanews.fr/)

Use the space in your resume, and use it wisely. Align similar information (such as dates of employment) along the same margin throughout the resume. Feel free to italicize, bold, and/or underline text to make it stand out. Lines can be used to separate different headings and categories. Don’t use templates, but do get ideas from other resumes on the web.

The Relevance

So you’re applying for a tech support job, but the only club you’re in is McDaniel’s Puppy Club—not exactly the most relevant extracurricular activity.

When is this little guy ever not relevant? (source: http://homeinspectorreno.com)

However, this information can still be useful. If your resume has an area for activities, feel free to include those that demonstrate leadership. While you won’t be training a service dog in IT, most extracurricular activities show that you are a person who goes out of their way to do more than they’re required to do. They also give insight into your interests.

Are you wondering what else you should include? Executive positions in particular signal experience working with others and managing different aspects of an organization. Certifications, such as in CPR/First Aid or various software, also tend to help a resume. In any case, stick with listing specific activities and certifications—don’t just list generic traits like “dependable.”

The Last Piece of Advice

So you think you’ve got a good draft of a resume, but you’re hesitant in sending it off to an employer? Luckily there are a few extra resources for you to use on campus: The C.E.O. and The Writing Center!

The Center for Experience and Opportunity, located in the lower level of Rouzer, helps students with all aspects of career preparation (including resume writing)! They are the perfect people to look over your resume in conjunction with the Writing Center. Writing Center tutors who have experience writing their own resumes are available to look over YOUR resume as well. A second (or third, or fourth) pair of eyes looking over your resume, from professional and peer perspectives, can’t hurt! So go out there, type up a fierce resume, and get that job!

-Sarah, Peer Tutor

Yeah, it’s tempting, and it’s sooo easy. But don’t be rude and don’t be distracted. Even if you’re taking notes on one, laptops give off a vibe of disinterest. Better stick to pen and paper, if you can.

Yeah, it’s tempting, and it’s sooo easy. But don’t be rude and don’t be distracted. Even if you’re taking notes on one, laptops give off a vibe of disinterest. Better stick to pen and paper, if you can. This seems obvious. However, a little reading every night will soon get you not only caught up to the class material, but beyond it. Once it’s a habit, it will feel weird not to read. Make a Buster-esque contraption to keep you awake, if you must.

This seems obvious. However, a little reading every night will soon get you not only caught up to the class material, but beyond it. Once it’s a habit, it will feel weird not to read. Make a Buster-esque contraption to keep you awake, if you must. Professors love when you go to office hours. LOVE. They can talk and help you out so much more when they have your attention past the mandatory 3-hours-per-week. And if you’re in an upper-level math class (speaking from experience here), you’ll never get an A without this.

Professors love when you go to office hours. LOVE. They can talk and help you out so much more when they have your attention past the mandatory 3-hours-per-week. And if you’re in an upper-level math class (speaking from experience here), you’ll never get an A without this. Don’t be that student and talk all of the time, but put yourself out there and thoughtfully ask or answer a question each class meeting. Your professor will remember you as a reliable class contributor.

Don’t be that student and talk all of the time, but put yourself out there and thoughtfully ask or answer a question each class meeting. Your professor will remember you as a reliable class contributor.