Commas are probably the second most feared punctuation mark in the English language, right next to the semicolon. There are lots of myths floating around about when you should and should not use commas. We’re here to set the record straight. Whenever you have a question concerning whether or not you should use a comma, just come on back to this blog post. You’re sure to find the answer.

First, let’s talk about the biggest myth in the entirety of comma lore.

Commas do NOT get put where you feel that there should be a pause. No. Wrong. Stop.

Believe me; if a sentence “sounds like” it should have a pause, most fluent speakers/readers will put one there, even without the comma. Commas serve a much more grand purpose.

Commas can be imperative to give the sentence meaning and nuance. Here are ten simple rules to help you master the comma:

- Two Independent Clauses With a Coordinating Conjunction

…what?

Let’s break that down. An independent clause is essentially a handful of words that could stand alone as a sentence. That means that they have a SUBJECT and a PREDICATE. Here are some examples:

- I wrote a blog.

- The blog is helpful.

- Everyone should read my blog.

Now, you can combine independent clauses (sentences) if they are closely related. We do this all the time, and they are commonly referred to as compound sentences. THAT’S what we’re talking about when we say two independent clauses with a coordinating conjunction.

But, what’s a coordinating conjunction?

Answer: FAN BOYS

Explanation: For, And, Nor, But, Or, Yet, So. FAN BOYS.

Fan boys are those little words that we use ALL THE TIME. They group things together (like clauses). Here are some examples:

- I wrote the blog, and it is helpful.

- Everyone should read my blog, so I shared it on Facebook.

- Everyone read my blog, but now everyone thinks I’m a nerd.

As you can see, whenever we used one of those coordinating conjunctions, we have to have one of those commas there.

One more thing.

Look at a sentence like this:

I wrote the blog, and I shared it, and now everyone hates it, so I tried to delete it, but I caught my computer on fire instead.

This is also a problem. This is a RUN-ON sentence. Even though it has all of the appropriate commas, compound generally only allow for two sentences being combined at a time with commas and conjunctions. Just break it up.

One down! Let’s keep going.

- Two Independent Clauses WITHOUT a Coordinating Conjunction

This is actually a time when you do NOT use a comma. We’ve already looked at what independent clauses and conjunctions are, so let’s move right into an example sentence:

I keep running out of example sentences, I should look some up on the Internet.

This looks deceptively correct. However, there is NO conjunction (FANBOY).

So…now what?

This is where the most feared punctuation mark comes in: the SEMICOLON. Whenever you have to independent clauses (complete sentences) stuck together without a conjunction, use a semicolon like so:

I know how to use semicolons now; I fear them no longer.

That was easy. On to rule three!

- Introductory Adverbial Phrases (IAPs)

Disclaimer: I don’t know if this is the technical term or not (and I don’t exactly care), but it’s a good term, so I’m going to use it.

Let’s break it down. A phrase is like a clause, but it doesn’t have the SUBJECT and a VERB, it just has one or the other, and it certainly could not stand alone as its own sentence. Here are some examples:

- Before writing

- In the morning

- Despite being a master in all things grammar

- Unfortunately

As you can see, IAPs can be as small as a single word or quite wordy.

IAPs occur at the beginning of a sentence. (That’s why they’re called introductory.)

Earlier, we talked about SUBJECT and PREDICATE. Technically, IAPs are part of the PREDICATE (the second half of the sentence). This is because IAPs act as adverbs (hence, adverbial); adverbs describe verbs, which are the fundamental parts of PREDICATES.

Because the IAP is separated from the PREDICATE, you need to have a comma after it. It helps the reader to see that it is not a part of the subject and can avoid troublesome confusion. Here are some examples:

- Before writing, I also do fifty pushups.

- Unfortunately, I cannot actually do fifty pushups.

Here’s an example of how not having that comma can cause confusion:

After walking the dog sat down.

“Walking the dog” is a common phrase. However, that’s not how those words are being used in this sentence. There wasn’t someone walking the dog; the dog was walking and then sat down. It should look like this:

After walking, the dog sat down.

Any questions? Good. Let’s move on.

- Dependent Clauses

We’ve mentioned clauses before. They have SUBJECTS and PREDICATES. They can stand alone as independent clauses.

So what makes a clause dependent?

Dependent clauses are things that could stand alone as complete sentences, but they have a word or two in the beginning that makes them unable to do so. Here are some examples; notice how they could stand alone with the first word(s):

- Although I do like writing

- Before I finish these examples

- Even though this is the last example

Just like IAPs, these dependent clauses act adverbially and are technically part of the PREDICATE. Ergo, they must have a comma before them for the same reason as IAP.

Easy enough, right? Right. Onward.

- Compound Predicates

This is the second rule where you do not need a comma. As we’ve mentioned quite a few times before, sentences have SUBJECTS and PREDICATES. In a circumstance where you have a compound predicate, you have a sentence with one SUBJECT performing two actions (two PREDICATES, if you will). Here are some examples:

- I wrote this blog and quit my job.

- I realized what a stupid idea that was and begged Josh for my job back.

- Josh was wonderful and gave me my job back.

Notice how each sentence could be separated into two sentences, like so:

- I wrote this blog. I quit my job.

And so on.

Because there is no new subject for the second action, you don’t put a comma after the coordinating conjunction like you normally would.

But there’s always a catch…

If you restate the subject, then you have to have a comma (even though technically it’s still the same subject). Here’s an example of that:

- I wrote this blog, and I quit my job.

English…

- Series (The Oxford Comma)

One of the most violently heated debates in English communities (and the eponymous title of a great Vampire Weekend song) is the use of the Oxford Comma.

The Oxford Comma is the last comma in a series of things. For example:

- There nice commas, mean commas, and Oxford Commas

- I need butter, milk, and eggs.

- I need another list that is easy, fast, and uses an Oxford Comma.

Now, the gradual decline of the Oxford Comma is often traced back to publication companies saving a few cents (and page space) for everything they printed (which added up). It was considered “irrelevant”.

They are wrong.

Here’s why.

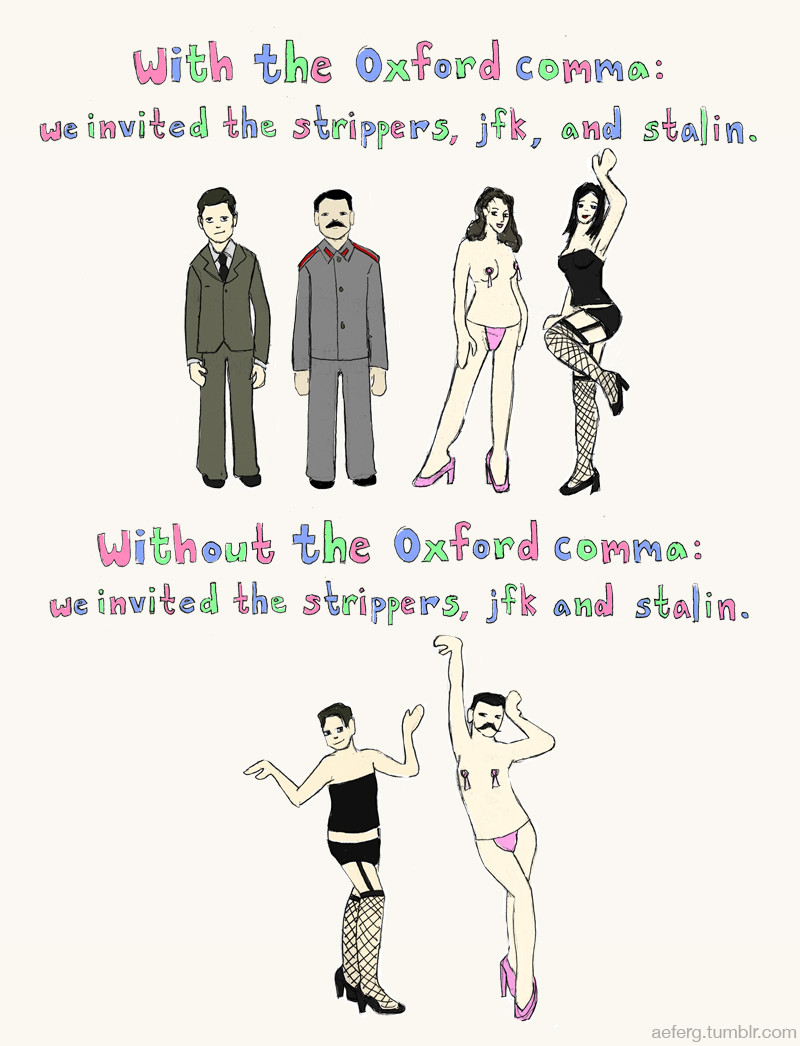

Courtesy of jfkandstalin.wordpress.com

Without the comma, it’s hard to tell whether or not the last two items are independent of them selves (items in the list), or an appositive for the item before the last comma. Here’s an example:

Get it? Without the Oxford Comma, you can’t tell if JFK and Stalin are two more things, or just more information about the first thing (strippers).

Two more. Let’s go. I’m going to lump the last two together because they are so closely related.

- Nonrestrictive Modifying Phrases/Appositives

- Restrictive Modifying Phrases/Appositives

More random English words. Let’s break it down.

Modifying phrases and appositives are words (or just a single word) that provide additional information about the subject. Modifying phrases are adjectival (describing how it is), and appositives are nominal (describing what it is). Here are some examples with the modifying phrase/appositive bolded:

- My mastiff, Percee, weights more than I do. (A)

- My mastiff, which weights more than I do, tried to sit on me. (MP)

- The book lying on the table is my favorite book. (MP)

- Rowling’s book The Sorcerer’s Stone is the first book in the series. (A)

A keen observer will have noticed that one of the appositives and modifying phrases were highlighted, and one of each was not. Here’s why:

If the appositive or modifying phrase is information that influences your interpretation of the sentence, DO NOT use commas. If the appositive or modifying phrase is extra information, DO use commas. Let’s look at the previous examples.

- I only have one mastiff. Therefore, I cannot be referring to any other mastiff other than Percee (who actually does weigh more than I do). Therefore, it’s in commas.

- Once again, I only have one mastiff. It needs no more explanation.

- “The book” is vague. There is more than one “book” in the universe. I need to restrict my definition of “the book” to mean precisely the book that is on the table.

- Again, Rowling has written way more than one book. I want to know specifically which

Basically, if you can take out the appositive/modifying phrase, and the reader would still know EXACTLY what you’re referring to, surround it in commas.

Nonrestrictive=Needs commas

That’s it! You’re free!

See, that wasn’t so bad.

There are a few minor rules that you should know as well, like always putting commas after proper locations or in a “this, not that” style sentence. Also, always use commas when you describe something with more than one adjective (the tall, slender writer). Oh yeah, and if someone is a Jr. or Sr., put a comma after their name and before the Jr./Sr. (John Doe, Jr.). Don’t forget to also put commas at the end of quotes.

Now, you too can be a Comma Master!

–Tyler, peer tutor