Regardless of how much you may love or hate writing, starting a new project is always the hardest part. Sometimes all you need is the perfect prompt to spark your inspiration. Creative writing, whether it be for a book or just a quick scene, is a great way to practice your skills, and these prompts are a great starting point for creating your next writing project.

Silly Prompts

Writing can be easiest when you don’t take it so seriously. Use one of these funny prompts to create a silly scene that makes you laugh.

- Write the emails between a hero and a villain as they try to reschedule their battle due to a scheduling conflict.

- Write a story about a great historical figure learning how to use the internet. What do they find online when they Google themselves?

- Write about a woman who promised her firstborn child to several different witches. Now that a baby is on the way, she has to deal with a custody battle.

- Write a slow-burn love story that is narrated by a very impatient narrator.

- Recall your most embarrassing memory, and write a funny story about it.

- Create an overly dramatic poem about a household item.

Dialogue Prompts

Focusing on a conversation as the centerpiece of your writing can be super fun and impactful. Try using one of these dialogue prompts to inspire your next written conversation between characters.

- “I know what you did.”

- “From the day we met, I knew you’d hurt me eventually.”

- “I’ll come back for you, I promise.”

- “I regret a lot of things. Having this conversation tops the list.”

- “What’s going on?”

- “How should I know?”

- “Now, don’t be mad, but…”

- “I know you don’t have any reason to trust me, but… you need to know something.”

- “Tuesday is always the worst day to rob a bank.”

- “A hero would sacrifice you to save the world. I’m not a hero.”

Fantasy Prompts

Fantasy writing gives you the opportunity to create new worlds and realities. Use one of these other-worldly prompts to create a compelling tale or fable that sends your readers to another world of your own creation.

- Your family is chosen for a year-long stay at an outpost on a new Earth-like planet, but the people in charge don’t tell you how the atmosphere there will change you.

- An ominous letter arrives — along with one offering magical guardianship for you and the shop you inherited. More worlds than one are at stake.

- Your best friend at college is a highly intuitive rune-caster, and people seek her out. One querent pays her with a magical pendant that changes both your lives.

- The trees surrounding your new home remind you of something — or rather someone. One touch of your hand on a trunk, and you’re face to face with him.

- Thanks to your quick thinking during a crisis at the village market, you’ve been appointed as the bodyguard for the princess. The job proves more difficult than any mission you’ve ever had — but also more rewarding.

Sad Prompts

Creating a heart wrenching story is a great way to push yourself to the limits of your emotional writing potential. Try out one of these tragic prompts to create a tale that makes your readers feel something from your words.

- You’re a ghost haunting your own funeral.

- Soulmates exist in your universe, and you are meant to meet your one true love when you turn 18, but your birthday was a week ago and your soulmate is nowhere to be found.

- The main character receives a devastating diagnosis and decides to track down and try to reconnect with their estranged daughter and son.

- Write from the perspective of a dog being returned to the shelter by their family.

- You have a wonderful life and a wonderful family. Then you wake up from your coma and learn to accept that none of it was real.

Sometimes it’s hard to get back into the habit of writing for fun, but it’s important to remember that inspiration is everywhere. Even if none of these prompts caught your interest, you can always find ideas in what you see, hear, and read every day. Just remember to keep your mind open for possible jumping off points for your next creation.

Natalie Edwards | 2023

Procrastination is not laziness. It’s a tool our body uses to avoid negative feelings and discomfort. We can address our body’s instinct to evade by equipping ourselves with more tools to get the results we want (and maybe even enjoy it along the way). It’s possible and rewarding to break the avoidance cycle and create work we are able to produce and proud to share.

Often, when we get an assignment, it can feel daunting, and the end result feels far from reach. We think of completing the end goals and not all the little goals we will get to accomplish along the way. Progress happens one keyboard punch and pencil scribble at a time, so don’t try to tackle it all once.

Break down large or long-term projects into actionable steps. By making smaller goals, you’ll be able to appropriately plan and allocate your time, use checkpoints to gauge your progress, and create momentum with each goal you get accomplished. This is a skill that will help whether you are renovating your house, completing a project for a boss, or writing an essay for class. You can visit the Writing Center and develop the skill of breaking down big goals into ones or get started with a class project using the assignment calculator.

Each time you identify a task, try to identify a resource you can utilize, too. Included in your tuition are library research assistants, academic counselors, Student Accessibility and Support Services, STEM tutors, Writing Center tutors, deans, professors, and more, all ready to offer support.

Chunk the time you spend working, with the pomodoro Technique. The Pomodoro technique addresses many of the mishaps that sometimes throw us off track: deadlines too far away to incentivize our dedication to the assignment; working past the point of optimal productivity and not being efficient with our time; feeling overly optimistic about how much work you can do and getting defeated when it doesn’t happen.

The Pomodoro Technique was developed in the late 1980s by Francesco Cirillo who was struggling to complete his assignments. Feeling overwhelmed, he committed to studying with full focus for just 10 minutes. He found a kitchen timer shaped like a tomato (Pomodoro in Italian) to keep track, and so, the Pomodoro technique was created. Here’s how you can do it, too.

- Create a to-do list or identify a single task.

- Set a timer for 25 minutes (or use this neat website equipped with work sprints and breaks) and focus on the work at hand until the timer rings.

- When the session is over, record what you completed.

- Then, enjoy a five-minute break.

- After three or four Pomodoros take a restorative 15-30 minute break.

Once you have started the pomodoro, the timer must ring. Do not break the session to check emails, chats, or texts. If you have a thought not relevant to the task at hand, jot it down and come back to it later. If distractions crop up, take note of them and consider how to prevent them in future sessions.

To optimize your pomodoro breakdowns, group together small tasks that will take less than 25 minutes to complete so you can do them in one session. Keep a note of the length of time actions end up taking you. You might not get the time break down right the first time you create your pomodoro to-do list! But, over time, you will learn how much time things take and you will be able to masterfully plan your time. For me, this has reduced a lot of stress, because it’s easier to plan pomodoro during your day than thinking of some open-ended completion of an assignment that has no bounds but a far-off due date. You can even use this for tasks you might be avoiding, not related to school, like cleaning up your room or filing taxes. After all, it’s just 25 minutes, the less enjoyable activity will end when the timer rings!

Molly Sherman | 2021

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/.

At face value, memorizing facts about a topic can be a daunting, even frustrating, task. Even worse, much of this information remains in our minds for only just about as long as the duration of the exam we’re cramming for.

Tired of the monotony of flashcards or simply rewriting notes? Why not try writing about the topics instead.

Although this can be a challenge when undertaking topics that don’t ignite much enthusiasm, the work that one must do with content in order to write a short article, or even a full essay, helps one transform into a practical expert on the topic.

Research

Writing begins with a research stage, which requires us to review everything we’ve previously learned about a topic, or variety of topics, then build on it. In essence, this is much like review before a test, but we can even learn some new factoids or gain additional perspectives that we haven’t previously considered during this stage.

Organizing Information

Next, we must begin to organize the information from our research. This again compels us to review the content. Gradually, we will start to take note that we are memorizing quite a bit of the content. At this step, we gain understanding of how different aspects of the topic relate to each other by grouping them into subtopics. This creates a roadmap that makes sense to our minds regarding the various pieces of information we are memorizing.

Outlines

The connections we’re forming are again reinforced through the creation of outlines. By creating a guide of ideas, we see bite-sized pieces of information rather than a stack of notecards or several pages of notes – much less overwhelming than before. By this stage, we’ve had to go through the information several times, but since we create something each time our boredom is minimized.

Writing!

Now that we have an outline, we’re ready to write. As this is only being used as a studying technique, we have absolute freedom in terms of how we want to write. This creates less pressure than many other academic situations. This is the fourth time we have made our way through our info in this process alone. By now, we have learned quite a bit. In proofreading this essay, we are able to repeat this process yet again.

Now, we have studied AND we’ve gotten valuable practice writing with less academic pressure. A win-win.

Kyle, Peer Tutor

Let’s be honest, most of us tell ourselves we will definitely start writing at a certain time of the day, and by the time it comes, we find ourselves sitting in front of our computer, staring at a blank Word document (almost blank! It probably has our name on it and an earlier date so it looks like we started earlier than the night before it’s due). After a while, you find yourself writing, but soon enough you are checking Instagram, or texting, or doing anything remotely entertaining to distract you from your work. Sound familiar? So how do you remain focused once you’ve started? Here are some tips!

- Find a good place to write. This may sound cheesy, but I can’t stress this enough. Find a place that’s conducive to writing for you. Some people get severely distracted in loud places, while some others can’t stand to sit in silence. Figure out what kind of person you are and find that place where you’ll be comfortable and feel like you can conquer anything.

- Accept the fact that, yes, you could be doing something more fun, but this assignment needs to get done. Many times, merely knowing that we could be relaxing instead of doing work creates writer’s block, making it impossible to concentrate. Let go of the tension that those feelings are causing and accept the assignment as it is. You’re in college now, you will get through this assignment and many more, so accept it and get to writing!

- Try not to think about how much you have left. I completely understand the feeling of dread you get when you look at how much you’ve written and it’s not even close to the page limit. Don’t get stuck! The more time you think about that, the less time you spend writing. Look at what you’ve written, give yourself a pat in the back for getting something done, and keep going!

- Give yourself breaks. Let yourself get distracted for 5-10 minutes, but stick to a schedule. Write for a while, then give yourself a break. I know turning off your phone sounds like torture, and I know the urge to check all your social media grows by the minute, but if you stick to a schedule you are more likely to get stuff done. You can even use these shorts breaks as a reward. You go, you!

- Get up! Ultimately, if your mind is wandering too much, go take a walk. Get some coffee or water, stretch your legs, and think about something else. By the time you come back to your computer, you are bound to feel recharged and have some fresh ideas.

- Visit the Writing Center! Just saying, if you come see us, you’ll have little choice but to focus on your assignment—at least for that hour.

Sometimes writing is a struggle for all of us, and that’s okay. But learning how to concentrate on your writing will help you in the long run. It may not be easy at first, but I’m sure you’ll get there. Good luck!

Mirii Rep, Writing Center Tutor

For everyone who may want to write about literature (English majors or otherwise), here’s a quick primer on some of the most popular schools of literary study, with examples of their application to William Shakespeare’s Hamlet.

Image from mhpbooks.com

Formalism: This is the literary field you were most likely taught back in high school. This study focuses on solely the language provided within a given text, rather than historical context or authorial intent. This method includes analyzing plot elements, characters, diction, and poetic devices such as metaphor and allusion.

Example: When Hamlet says “To die; to sleep…” (3.1.68), he is using metaphor to compare dying to sleeping, and thus makes death seem less frightful and complex.

Structuralism: Structuralism focuses on how plot elements may give structure to a text, often by analyzing binaries that exist within a text. Like Formalism, Structuralism focuses solely on a text itself, not historical context.

Example: We see a dichotomy of characters within Hamlet, those who act and those who think/hesitate/do not act. Laertes and Claudius are men of action (fighting or killing to suit their needs), whereas Hamlet tends toward inaction (hesitating to kill Claudius as he prays.)

Deconstruction: When Structuralism gives us binaries, Deconstruction breaks them down. Deconstruction also analyzes the instability of language, as word meanings may change over time or mean several things within one usage.

Example: Although, as our previous example demonstrated, Hamlet tends toward inaction, he tends toward actions in some scene, such as when he stabs Polonius through a curtain. We can also ask what exactly “action” means – is it solely deeds, or does speech count as well?

New Historicism: New Historicism looks at the realities of the time period a text was written in to find meaning. New Historicism seeks out primary sources to give us description about what life was like for the author during their life in their era and their home.

Example: What was life like for Danish royals during the Renaissance? Why did Shakespeare, an Englishman, choose to write about Denmark? Succession disputes are at the heart of Hamlet’s plot, is this commentary on the real-life succession crisis following the death of Queen Elizabeth I that Shakespeare lived through?

Art by John William Waterhouse

Feminism: Feminist theory analyzes women within a text. This can manifest as analyzing female characters themselves, or attitudes toward women, or how women are placed within power structures of the text, etc. Feminist studies has since transformed into Gender Studies, which analyzes both men and women in a text, as well as what constitutes the masculine and the feminine in a text.

Example: Only two women appear within Hamlet: one his mother, Gertrude and one his girlfriend, Ophelia. Hamlet harasses his mother, believing she has something to due with the murder of his father (she does not), and spurns Ophelia as a part of his scheme to “act crazy.” We can easily see that women do not have much power within the play.

Queer Theory: Queer Theory came out of Gender Studies, and focuses on depictions of non-normative sexuality that oppose dominant attitudes about sexuality. Queer Theory also analyzes general inversions of dominant constructs within a given text.

Example: Is Hamlet’s relationship with Horatio homoerotic? The Prince tells Horatio that he is held close in his heart, and Horatio eulogizes the dying Hamlet with the touching “Goodnight, sweet prince” (5.2.397).

Psychoanalysis: Having begun with Sigmund Freud, Psychoanalytic Theory attempts to understand the unconscious and subconscious of authors as their desires may manifest within literature. While some of the most famous applications of Psychoanalytic literary criticism involve the Oedipus Complex, this field also studies the id, ego, and superego; dreams; reality versus fantasy; and death wishes/death avoidance.

Example: “Hamlet and Oedipus,” a book by Ernest Jones, claims that Hamlet’s desire to kill his uncle is in part due to his repressed sexual desire for his own mother. This theory about Hamlet and Gertrude’s relationship can also be seen in several adaptations of the play, such as Mel Gibson’s Hamlet.

Marxism: Marxism analyzes both structures of control and circulation of capital. Marxism asks who has the power and what gives them that power within any given work of literature.

Example: The major players of the text have considerable wealth, either belonging to the royal family or having some kind of noble blood. Non-royal characters, such as Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, are expendable, their deaths off-screen and holding little impact. This fact demonstrates the valuing of those with capital over those without within feudalism/capitalism.

In academia, you will rarely find scholarly articles that use only one method of analysis. It is common, for instance, to see a scholar take a Marxist, Feminist, and New Historicist approach to a text, or maybe a Queer and Deconstructionist approach. This breakdown is simply to help identify such approaches, and perhaps inspire you to analyze literature under these approaches on your own.

-Summer, Peer Tutor

Chicago Manual Style. Though you may hope that your professor is requesting that you turn in a deep dish pizza with your finished essay, this is not the case.

Image courtesy of cookdiary.net

While Chicago style formatting is not as delicious as deep dish pizza, it is no cause for alarm. Some people cling to MLA as it is familiar to them, but Chicago is very easy, and has a cleaner look to it on the page. Do not worry, you too can learn this wonderful formatting style!

Here are simple tips for formatting your paper in Chicago style:

-If you are talking about a book or the title of a periodical, italicize it.

-If you are talking about an article or the title of a chapter, it get less fancy “quotation marks.”

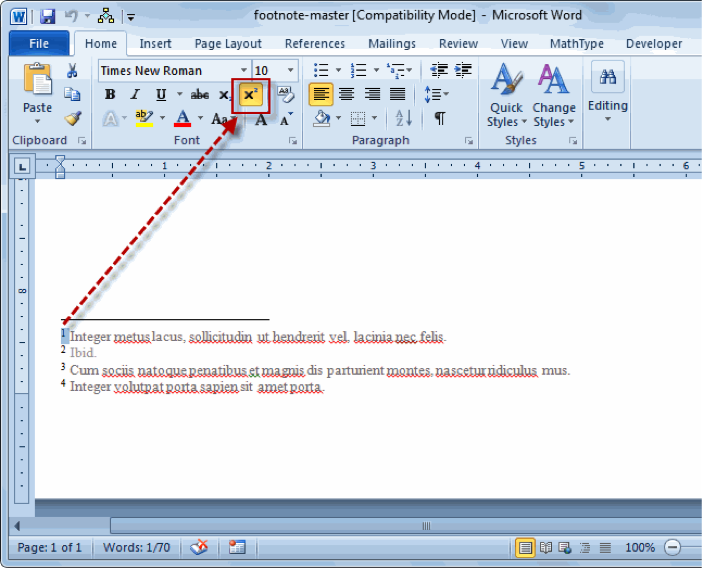

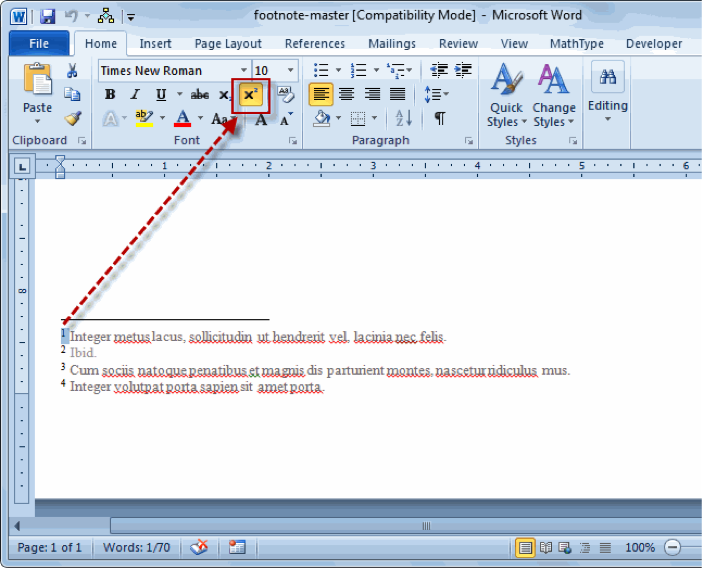

-When you cite a source, place a superscript number at the end of the sentence. This number will correspond to a footnote at the bottom of the page. Not sure how that works in Word? It should look something like this:

Image courtesy of community.thomsonreuters.com

How do you format these citations or in-text citations you ask? Never fear! It is also quite simple.

For the footnote:

1Firstname, Lastname. Fancy Title of Book. (Fancy place of publication: Publisher name, publication year), page number(s).

1Jane Austen. Sense and Sensibility. (New York: W. W. Norton and Co., 2002), 254.

For the bibliography:

Lastname, Firstname. Fancy Title of Book. Place of publication: Publisher name, publication

year.

Austen, Jane. Sense and Sensibility. New York: W. W. Norton and Co., 2002.

The formatting for an article in a periodical is also very similar and simple.

For the footnote:

2Firstname, Lastname. “Fancy Title of Article,” Capitalized Journal Title. issue number, volume number (year of publication): page number(s) that you are citing.

2Misty, Krueger. “From Marginalia to Juvenilia: Jane Austen’s Vindication of the Stuarts.”

Eighteenth Century: Theory and Interpretation. 56, no. 2 (2015): 250.

For the bibliography:

2Lastname, Firstname. “Fancy Title of Article,” Capitalized Journal Title. issue number, volume

number (year of publication): page number(s) cited.

2Krueger, Misty. “From Marginalia to Juvenilia: Jane Austen’s Vindication of the Stuarts.”

Eighteenth Century: Theory And Interpretation. 56, no. 2 (2015): 243-259.

More tips for the Bibliography:

-Just like with other citation methods, your bibliography should be in alphabetical order.

-If there are 2-3 authors, write out all of their names. If you have 4-10 authors, then still write out all of their names. However, just use the first of the names and “et al” in your footnotes.

If you have other questions about Chicago Manual Style, another wonderful resource is the OWL Purdue.

Happy citing!

-Hannah, peer tutor